- Home

- Tim Alberta

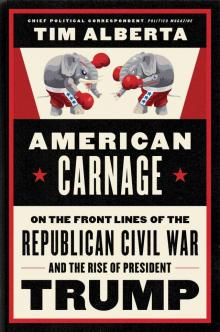

American Carnage Page 3

American Carnage Read online

Page 3

Increasingly, Bush’s legacy was feeling treasonous to small-government Republicans: prodigious spending, endless war overseas, rising debt and deficits, a massive federal intrusion into K–12 education, the biggest entitlement expansion since the Great Society. “Who in the end prepared the ground for the McCain ascendency? Not Feingold. Not Kennedy. Not even Giuliani. It was George W. Bush,” conservative pundit Charles Krauthammer wrote in the Washington Post after Romney quit. “Bush muddied the ideological waters of conservatism.”6

Perhaps most irritating to the base, Bush had proclaimed upon winning reelection that he had “political capital” and would spend it on two things he barely mentioned during the 2004 campaign: privatizing Social Security and reforming the country’s immigration system.

Paul Ryan, a young congressman from Wisconsin, had distinguished himself as the most outspoken advocate in the House of Representatives for making changes to Social Security. He found himself at once excited and perplexed when Bush suddenly pledged to tackle the issue. “He didn’t really talk about Social Security at all,” Ryan says. “The campaign was more about security—you know, 9/11, three Purple Hearts, the swift boat stuff. So, I remember him declaring what he wanted to do, which I thought was spectacular. But I also thought, gosh, he didn’t really till the field for this.”

Soon, Ryan was aboard Air Force One with Bush, flying to Wisconsin for an event aimed at selling the Social Security overhaul. Of all the Republicans in the state’s congressional delegation, he was the only one to accompany the president. “They all thought it was too risky,” Ryan recalls.

His colleagues were smart to sense trouble: Bush’s plan to create personalized accounts, while fashionable among the conservative intellectual class, was a nonstarter with much of the party’s base, particularly blue-collar workers, middle-class earners, and the elderly. The backlash was so harsh, in so many congressional districts, that Speaker Denny Hastert and his GOP leadership team refused to give the president’s bill a committee hearing.

The failed Social Security push was crucial—not just for what it foretold about the party’s fraught relationship with entitlement programs, but for its dooming of immigration reform as well. White House officials had vigorously debated which initiative to lead the second term with; Social Security reform, the heavier lift, ultimately won out. By late May, when House GOP leadership apprised members of the summer schedule, Bush’s proposal was dead.

The time and momentum lost proved critical: Democrats won back majorities in both chambers of Congress in 2006, leaving Bush weakened to sell an immigration deal to Republicans and the Democrats emboldened to hold out for something better. “The sequencing was off,” Karl Rove, Bush’s chief strategist, admits. “If we had done immigration first, it would have passed.”

The effort came tantalizingly close nonetheless: For much of 2007, Kennedy and McCain strong-armed their Senate colleagues while Democrat Luis Gutierrez and Republican Jeff Flake whipped support for a companion bill in the House.7 When it failed, some Republicans could argue honestly that they had done their part. Democrats were in control of Congress, after all, and given the rivalries within that party’s coalition (Blue Dog labor versus Green-minded progressives, Charlie Rangel’s Congressional Black Caucus versus Gutierrez’s Congressional Hispanic Caucus), the collapse of immigration reform looked to be a bipartisan feat.

But the GOP’s struggle with immigration was, and would remain, something more existential than any one legislative outcome might suggest.

The 2000 campaign was meant to signal a new era of Republican politics: warm, aspirational, inclusive. Bush spoke Spanish at events and promised to champion diversity as a core American quality. He fumed when his body man, a Texan of Hispanic descent, was pulled over in Iowa and hassled about his citizenship. Bush’s deployment of the term “compassionate conservatism” wasn’t merely an electoral ploy. The Texas governor, known to converse at length with hotel maids and interrupt dinner parties with Luke 12:48—“From everyone who has been given much, much will be wanted”—envisioned a presidency founded on principles of equality and charity. Tending to war-torn nations with medical assistance and refugee resettlement would be a priority, as would tending to war-torn American communities with education reforms and prisoner reentry programs.

What Bush couldn’t foresee was September 11, 2001, and how the attacks would not only alter his own priorities but also contribute to a changing psyche on the American right.

“The term ‘compassionate conservatism’ ticked off conservatives,” recalls Jim Towey, the director of faith-based initiatives in Bush’s White House. “I’d go into meetings on Capitol Hill with members who didn’t have any African Americans in their districts and talk about prisoner reentry or drug treatment with them. They could not have cared less. Their eyes would glaze over, like, ‘Why are you talking to me about this?’” When Bush would engage those lawmakers on the issues himself, Towey recalls, “The president would be told, ‘You sound like a Democrat. All this stuff about poor people, immigrants, refugees—this is how Democrats talk.’”

Much of this dissension within the Republican ranks boiled below surface level. Although racism was alive and well, and fears of ethnic targeting spiked after 9/11 (prompting Bush to visit a mosque and declare Islam a peaceful religion), xenophobia did not dominate the national political environment. That began to change after 2004. Bush believed his reelection was a mandate to do big things, including immigration reform. But his base saw it very differently. “The 2004 campaign was about who’s keeping us strongest and who’s keeping us safe, not who’s making for a more just society,” Rove says.

Pete Wehner, who led Bush’s Office of Strategic Initiatives, says “there was a shift” after the president announced his intention to change U.S. immigration policy. “If you read the books by Rush and Hannity prior to 2005, you don’t find anything on immigration. There was nothing on talk radio,” Wehner says. “But our base was changing. Some of it was tied to 9/11. Some of it was tied to economic insecurity. Some of it was tied to a sense of lost culture for a lot of people on the right. Those attitudes on immigration were proxies for a lot of other things.”

Bush saw it sooner than most. Early in his second term, while meeting with a few trusted advisers, the president confided that he was worried about some interconnected trends taking root in the country—and most acutely within the Republican Party. There was protectionism, a belief that global commerce and international trade deals wounded the domestic workforce. There was isolationism, a reluctance to exert American influence and strength abroad. And there was nativism, a prejudice against all things foreign: traditions, cultures, people.

“These isms,” Bush told his team, “are gonna eat us alive.”

THE WHEELS WERE COMING OFF BUSH’S WHITE HOUSE BY THE TIME the 2008 primary got under way.

Any two-term president’s party craves fresh perspective after eight years, but the administration’s snowballing ineptitude—the half-baked nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court, the abysmal handling of Hurricane Katrina, the gross negligence at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the vice president sending a buckshot into his hunting buddy’s face, among other misadventures—imposed a unique urgency on Republican candidates seeking distance from the incumbent.

For Ron Paul, the iconoclastic libertarian from Texas, this meant denouncing foreign intervention and relinquishing the role of global policeman. For Huckabee, the key was merging folksy Christian appeal with folksier populism, arguing that changes to Social Security or Medicare would unfairly punish the people whose hard work funded the programs in the first place. For Romney, the darling of the right, it was all about fiscal responsibility: balancing budgets, reducing spending, streamlining government agencies.

Then there was McCain. His candidacy was built less on policy specifics than on biography, implicit to which was a message of preparedness. McCain was hardly a Bush ally; the two battled ferociously for the Republica

n nomination in 2000, a race that climaxed with a smear campaign in South Carolina alleging that McCain had fathered a black child out of wedlock.8 Yet the senator had tied his presidential hopes to the troop surge in Iraq. And despite its decided unpopularity when it was announced in January 2007, the surge worked, stabilizing a country that had been ravaged by sectarian violence since the U.S. invasion in 2003.

As it became clear that the party would nominate someone who, on two defining issues (immigration and Iraq), was in lockstep with a deeply disliked president, Republicans couldn’t help but take out their frustration on McCain.

Not that he didn’t have it coming. Years of bucking the party line and antagonizing the right had finally caught up with McCain by the time he became the party’s presumptive nominee. That spring, when the Arizona senator dispatched his longtime colleague and respected fiscal hawk Phil Gramm to meet with House conservatives on his behalf, the former Texas senator (and would-be treasury secretary in a McCain administration) got an earful.

“Tell me something,” Patrick McHenry, a young Republican from North Carolina said to Gramm. “Why should I not be physically ill at the prospect of a President John McCain?”

Taken aback, Gramm gave the only reply that passed the smell test: “Conservative judges.”

The party’s new standard-bearer wanted to show a united Republican front as he pivoted to the general election. But it was proving elusive. When McCain met with conservative movement leaders throughout the summer, seeking to soothe their concerns and coalesce their support, he was hammered with a constant refrain: He needed a conservative, pro-life running mate to offset the right’s reservations about him.

The problem was, none of the conventional “short list” choices was appealing to McCain. He didn’t care for Romney. He couldn’t relate to Huckabee. He thought Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty and Florida governor Charlie Crist were boring. In a contest against Barack Obama, the dynamic young Illinois senator who had outlasted Hillary Clinton and was marching toward history as the nation’s first black president, McCain would not win by being conventional.

What McCain wanted to do—what he told senior aides he would do—was pick his close friend Joe Lieberman.

A former Democrat turned independent who shared McCain’s hawkish foreign policy views, Lieberman would accentuate the Republican nominee’s strengths: independent-minded, muscular on national security matters, experienced, and ready to govern on day one.

It wouldn’t be that simple, however. Lieberman was pro-choice, an apostasy that McCain’s advisers warned could shatter his uneasy alliance with the GOP base. McCain learned this lesson for himself in mid-August after suggesting to the Weekly Standard that former Pennsylvania governor Tom Ridge was under consideration, noting that Ridge’s pro-choice position wasn’t a deal breaker.9 If this were a trial balloon, its pop registered on the Richter scale. The blowback—delegates threatening to defeat his choice at the convention, activist leaders saying their constituencies might sit out the election entirely—convinced McCain to heed the advice of his brain trust. Lieberman could not join the ticket.

It was time to panic. With the convention weeks away, the presumptive Republican nominee had no clue whom to choose as his running mate. Obama was consistently leading in the polls, and all the fundamentals—unpopular president, dragging economy, change election—were in his favor. The circumstances called for a bold stroke, a daring maneuver from the maverick. But the base would revolt over Lieberman. McCain felt helpless, irritated by the quandary and underwhelmed by his options. Who could possibly shake up the race and excite conservatives?

CONGRESSIONAL REPUBLICANS SPENT THE SUMMER ATTEMPTING TO shift the national argument from two wars and a looming recession to friendlier terrain: energy. With gas prices soaring and Democrats opposing new means of exploration, the GOP tried to frame an exaggerated contrast between the parties: one looking out for the far-left environmental lobby, one looking out for working families struggling to fill their tanks.

As part of the initiative, Ohio congressman John Boehner, who after the 2006 election had succeeded Hastert as the top House Republican, led a delegation of GOP legislators to tour energy sites in Colorado and Alaska. When the group arrived on the remote North Slope, they were met by a forty-four-year-old first-term governor most had never heard of. By the time they left, the men in the group were remarking to one another: Sarah Palin had a great physique.

Nobody returned to Washington raving about Palin as a prodigy. To the extent that she was recalled by the congressmen to their friends and staff members, it was that governor of Alaska is a knockout. The thought of Palin as national timber simply did not compute. She had spunk and self-confidence by the barrelful, but was far removed, physically and intellectually, from the debates driving Washington policymaking. The only prominent Republican hawking Palin for VP was Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol, who had met her on his own trip to Alaska. When Kristol called Palin his vice-presidential “heartthrob” on Fox News Sunday, just days after the delegation trip concluded, the congressmen sneered at the prospect of a pinup following in the footsteps of Dick Cheney, Nelson Rockefeller, and Hubert Humphrey.

What they didn’t know was that McCain’s campaign had been in contact with Palin.

It seemed unserious at first; McCain had met Governor Palin just once, and briefly, at a meeting of the National Governors Association. But with time running out, and the door suddenly slammed on the prospect of either Lieberman or Ridge, McCain’s team flagged Palin as a last-second Hail Mary.

Intrigued, McCain spoke with Palin by phone on August 24—eight days before the GOP convention was set to convene in the Twin Cities of Minnesota.10 The call was ostensibly to quiz the Alaska governor on her answers to McCain’s vetting questionnaire. But for Steve Schmidt, the campaign’s pugilistic senior strategist and its staunchest pro-Palin advocate, it was meant to get McCain comfortable with the only checks-all-the-boxes option available. Four days later, after a last-ditch plea from McCain to his staff to let him pick Lieberman, Palin arrived at the senator’s Sedona ranch for a face-to-face meeting. The next afternoon, inside a rowdy arena in Dayton, Ohio, John McCain introduced Sarah Palin, a woman with whom he’d spent a sum total of a few hours, as his choice for the vice presidency of the United States.

“WHO?” OBAMA ASKED, FLYING TO CHICAGO FROM DENVER FOLLOWING his own party’s convention.

David Axelrod, the Democratic nominee’s chief strategist, was at a loss. His team had performed extensive opposition research on eight potential VP selections, and Palin wasn’t one of them. He told Obama, sheepishly, that he didn’t know much about the Alaska governor.

“Well, why did he pick her?” Obama asked.

“Because she’s a woman,” Axelrod replied, “and because he wants his campaign to be about change, too.”

Obama thought for a moment. “Yeah, but this whole running for national office thing is really hard,” he said. “She may be the greatest politician since Ronald Reagan. Maybe she comes out of Alaska and handles this whole shitshow. But let’s give her a month and then we’ll see.”

Back in the nation’s capital, Bush had a similar reaction. “So, what do you make of the news?” the president asked Dana Perino, his press secretary, as they watched Palin’s introduction on television in the Oval Office.

“For a Republican woman, it’s really exciting,” Perino said, beaming.

“It is exciting,” Bush agreed. He took a lingering pause. “But she’s got no idea what’s about to hit her.”

Nor did the Republican Party itself. Practically overnight, Sarah Palin came to embody the most disruptive “ism” of them all, one that would reshape the GOP for a decade to come: populism.

THE ANNOUNCEMENT OF PALIN WAS SO RUSHED THAT PARTY OFFICIALS could not offer basic biographical talking points to inquiring reporters. Several of McCain’s own staffers mispronounced the Alaska governor’s name on conference calls the day of her rollout.11 The famously diso

rganized campaign was already ill-prepared for the convention, and now his staff was tasked with selling the American public on someone they themselves knew nothing about.

Amid this inferno, the coolest performer was Palin herself. If she was daunted by the expeditious leap from Alaska obscurity to international celebrity, it didn’t show. The governor was a born performer: warm, funny, charismatic, and devastatingly common. A union member’s wife and a mother of five, including an infant son with Down syndrome, Palin oozed relatability to middle America. She was not merely a breakout star; she was a political phenomenon.

Both in her Dayton introduction speech and in her address to the convention a few days later, Palin sent tremors through the Republican Party. Her combination of homespun magnetism and theatrical fearlessness was breathtaking. Inside the suite belonging to Boehner, who was serving as the convention’s chairman, party heavyweights whispered that she was Reagan reincarnate. Boehner was taking painkillers to manage sciatica and thought he might be hallucinating; this could not be the same small-state governor he and his colleagues had met just a few months earlier.

It was her, all right, and Palin was proving even more telegenic than any of those House Republicans could have imagined. After watching her onstage in Dayton, Roger Ailes, the chairman and CEO of Fox News, phoned one of McCain’s senior advisers. Ailes explained a process he used for scouting talent at other networks: He would flip through news channels and stop when a female anchor held his attention. “That’s what she just did for the Republicans,” Ailes said.

All eyes were on Palin. With the GOP’s new sensation dominating the headlines and turbo-charging the convention audience, it was easy to overlook who wasn’t in Minnesota: Bush.

McCain had kept a strategic distance from the White House since winning the primary, not wanting to aid Obama’s argument that he represented a third term for the current president. Bush was not offended, having embraced a gallows humor regarding his own unpopularity. But the McCain team’s decision to keep him away from the convention, with Hurricane Gustav approaching the Gulf and the wounds of Katrina still fresh, enraged some Republicans. “It was disgraceful. He’s the sitting president, the leader of the Republican Party for eight years, and he doesn’t get to speak?” says Sara Fagen, the White House political director under Bush. “It was a disgraceful moment for John McCain and for the Republican Party.”

American Carnage

American Carnage