- Home

- Tim Alberta

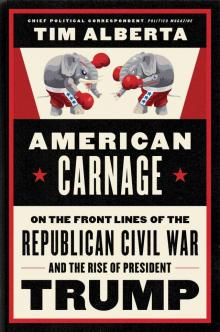

American Carnage

American Carnage Read online

Dedication

To Abraham and Lewis and Brooks:

Reject false choices. Think for yourselves.

Epigraph

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

—JAMES MADISON, FEDERALIST, NO. 51

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter One: February 2008

Chapter Two: January 2009

Chapter Three: April 2010

Chapter Four: January 2011

Chapter Five: January 2012

Chapter Six: December 2012

Chapter Seven: August 2013

Chapter Eight: April 2014

Chapter Nine: January 2015

Chapter Ten: September 2015

Chapter Eleven: October 2015

Chapter Twelve: January 2016

Chapter Thirteen: March 2016

Chapter Fourteen: May 2016

Chapter Fifteen: July 2016

Chapter Sixteen: October 2016

Chapter Seventeen: October 2016

Chapter Eighteen: November 2016

Chapter Nineteen: January 2017

Chapter Twenty: June 2017

Chapter Twenty-One: August 2017

Chapter Twenty-Two: January 2018

Chapter Twenty-Three: July 2018

Chapter Twenty-Four: September 2018

Chapter Twenty-Five: November 2018

Chapter Twenty-Six: December 2018

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

HOW DID DONALD TRUMP BECOME PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES?

Since the early morning hours of November 9, 2016, game attempts to solve this riddle have been subject to the same disorienting forces that came to define his political ascent: ideological bias and tribal loyalty, social alienation and demographic transition, institutional breakdown and political polarization.

There is a temptation not only to associate these things with Trump, but to blame him for the havoc they hath wrought on America and the world. Throughout his campaign for the presidency and in his first two years in office, Trump defied every law of gravity while shattering societal conventions that will prove difficult to repair. In so doing, he nurtured narratives of his own centrality to a bruising reconfiguration of modern American life.

Trailblazing as he might be, Trump is not the creator of this era of national disruption. Rather, he is its most manifest consequence.

IN PRESIDENTIAL POLITICS, THE CANDIDATE MUST MEET THE MOMENT. Barack Obama could not have won the White House with his dovish foreign policy platform in 2004, an election decided on the question of whom Americans wanted as their wartime president. It was not until 2008, with the country weary from intervention, and his heavily favored Democratic rival tainted with a vote for the Iraq invasion, that the electorate was primed for his candidacy.

Similarly, Trump’s appeals to America’s darker impulses would have fallen flat in 2000. The nation was too peaceful, too prosperous, too cohesive. All throughout history the world over, efforts to exploit anxiety have succeeded when there is anxiety to be found: times of war, financial despair, national disunity. The United States circa 2000 did not fit the bill. Even after winning the most disputed race in presidential history, with a grueling thirty-six-day Florida recount splintering the nation before the Supreme Court intervened on his behalf, George W. Bush entered office with a 57 percent approval rating—higher than the incoming marks of both his father, George H. W. Bush, and the previous Republican president, Ronald Reagan.

Eight years later, the scenery had changed. The country was trapped in two deeply unpopular military conflicts. It was shedding jobs at an alarming rate, particularly in the manufacturing hubs of middle America. And its electorate was increasingly bifurcated, with partisans estranged from one another not just ideologically but geographically and culturally as well.

Into this breach stepped Obama. He promised to heal these wounds, to reject the labels of “red states” and “blue states” and unify the country. It would prove an impossible task.

TO UNDERSTAND TRUMPISM IS TO UNDERSTAND THE DRAMATIC NATIONAL makeover of the previous ten years. When Obama was sworn in as president in January 2009, he opposed same-sex marriage. Facebook lagged behind MySpace in monthly Web traffic. Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie were the most famous couple on earth. Airbnb had just launched its website. Tiger Woods was the world’s most dominant athlete. Uber did not exist. Nobody had heard of the word gluten. The Twitter account @realDonaldTrump had not yet been created.

The ensuing decade saw a convergence of phenomena—economic displacement, technological innovation, civic upheaval—that fundamentally reshaped our politics. And nowhere was that change felt more acutely than inside the Republican Party.

Having moved to Washington in the twilight of Bush’s presidency, I found myself less fascinated by Obama and his incoming Democratic government than by the power vacuum in the GOP. Bush was leaving office with record-low approval and Republicans were headed into the wilderness. There was no vision, no new generation of leaders, no energy in the conservative base. One of America’s two major parties had gone politically bankrupt.

In the ten years since, covering Congress and campaigns, I have interviewed more than a dozen Republican presidential candidates, scores of GOP congressmen and senators and governors, hundreds of party activists and strategists, and countless voters all across the country.

I watched as the Republican Congress went to war with Obama; as the Tea Party rebranded the American right; as platoons of insurgent lawmakers came to Washington intent on its demolition; as the government was shuttered and pushed to the brink of default; as a group of renegades established themselves as an effective veto threat over their own party; and as the mutiny overthrew the most powerful man in the GOP, having already swallowed up his heir apparent.

A wave of revolution was cresting in the Republican Party. The only question was who would ride it.

THE NARRATIVE I AM SETTING FORTH IN THESE PAGES IS NOT MEANT TO be comprehensive. What I have attempted to construct is an account guided by my own coverage of what, until the spring of 2016, was commonly known as the Republican civil war, as told through the eyes of the combatants on the front lines.

Although this project was conceived in the middle of 2016, it was not until early 2018 that I began researching and reporting the new material that would form this book’s foundation. In the year since, I have interviewed more than three hundred people specifically for the purposes of this recounting. Those interviews, joined with my work over the previous decade, comprise the spine of the story you are about to read.

Wherever I have drawn from other sources of information, proper attribution and/or citation is provided.

Everything else is rooted in my own reporting. Most of the interviews were conducted on the record; any quote that appears in the present tense (“says”) is draw

n from original reporting, as are the past-tense quotes (“said”) that do not include outside attribution.

This book is fashioned not as a traditional work of journalism, but as a storytelling narrative. Portions of some interviews were conducted on deep background, giving me license to use the material but not attribute the source. In those instances, the only reporting I present in these pages is taken from sources with firsthand knowledge of the events and conversations in question.

At a time when truth is under attack, I have labored to verify every quote, story, and circumstance down to the smallest detail. In addition to hundreds of hours of taped interviews, I have also drawn from emails, audio files, contemporaneous memos, and other private records provided by sources whose identities I agreed to safeguard.

It is my hope that by reading this account of the political and cultural turbulence that rattled the nation during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, you will gain a more textured understanding of Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency—and of its implications for America.

TIM ALBERTA

January 2019

Prologue

THE RESOLUTE DESK IS CLEAN AND UNCLUTTERED, ITS WALNUT VENEER glimmering as rays of late afternoon sun dart between the regal golden curtains and irradiate the Oval Office. There are two black telephones situated at the president’s left elbow, one line for everyday communications within the White House and the other for secured calls with the likes of military leaders, intelligence officials, and fellow heads of state. There is a small, rectangular wooden box adorned with a presidential seal and a red button so minuscule that it escapes my eye until he pushes it, prompting only momentary distress over the impending possibility of nuclear apocalypse before a tidily dressed butler appears moments later and places a tall, hissing glass of Diet Coke in front of the commander in chief. Finally, there is a single sheet of paper, white dotted with red and blue and yellow ink, that the president continues to nudge in my direction. It proclaims the results of a CBS poll taken two nights earlier, immediately following his 2019 State of the Union address: 97 percent of Republican viewers approved of the speech.

“Look,” Donald Trump says, shoving the document fully in front of me, reciting the 97 percent statistic several times. “It’s pretty wild.”

It certainly is.

Pretty wild that Trump, a thrice-married philanderer who paraded mistresses through the tabloids and paid hush money to pinups and porn stars, could conquer a party that once prided itself on moral fiber and family values.

Pretty wild that Trump, a real estate mogul and reality TV star with no prior experience in either the government or the military, could win the presidency in his first bid for elected office.

And yes, pretty wild that Trump, who spent his first two years as president conducting himself in a manner so self-evidently unbecoming of the office—trafficking in schoolyard taunts, peddling brazen untruths, cozying up to murderous tyrants, tearing down our national institutions, weaponizing the gears of government for the purpose of self-preservation, preying on racial division and cultural resentment—finds himself in a stronger standing with the Republican base heading into the 2020 election than he did upon winning the presidency in 2016.

To be clear, the 97 percent statistic is meaningless: Presidents have long utilized the State of the Union tradition as a pep rally, vision-casting in ways designed to draw standing ovations and project the awesome power of the bully pulpit, leaving little for the party faithful not to love.

But Trump is not wrong when he boasts of the unwavering support he enjoys within the GOP. In fact, according to Gallup, he is more popular with his party two years into office than any president in the last half century save for George W. Bush in the aftermath of 9/11. Unlike with Bush, there is no connective national crisis to which Trump can attribute the allegiance of the Republican rank and file; to the contrary, Trump celebrated the two-year anniversary of his inauguration by presiding over the longest government shutdown in U.S. history, a climax of the absolutism that came to infect the body politic around the turn of the century and now appears less curable with each passing day. Even in this valley, with his overall approval rating sliding to an anemic 37 percent, Gallup showed Trump maintaining the support of 88 percent of Republicans. Sitting in his office in early February, less than two weeks since the reopening of the federal government, his overall approval rating has shot back up to 44 percent. Among Republicans, it’s steady at 89 percent.

That he has executed a hostile takeover of one of America’s two major parties—the one he never formally belonged to before seeking its presidential nomination—will astonish generations of intellectuals, think-tankers, and political professionals. But it does not surprise Trump.

A decade earlier, as a transition of political power coincided with a jarring suspension of America’s economic stability, Trump saw what many Republicans refused to acknowledge: Their party was “weak.” Not just weak in the sense of campaign infrastructure or policy positions, but weak in spirit, weak in manner, weak in appearance. The country was hurting. People were scared. What they wanted, Trump realized, was someone to channel their indignation, to hear their grievances, to fight for their way of life. What they got instead was George W. Bush bailing out banks, John McCain vouching for Barack Obama’s character, and Mitt Romney teaching graduate seminars on macroeconomics.

“Nobody gave them hope,” Trump says of these anxious Americans, enumerating the deficiencies of those three Republican standard-bearers who came before him. “I gave them hope.”

TO CONSIDER TRUMP’S RISE IS TO RECOGNIZE THE ESSENTIAL INGREDIENTS of American life: instinctual outrage and involuntary contempt, geographic clustering and clannish identification, moral relativism and self-victimization.

These conditions began to shape the modern political era dating back to the mid-1990s. There was the zero-sum warfare practiced by then-Speaker Newt Gingrich, who encouraged Republicans to use words such as “traitors” and “radicals” to describe their political opponents. There was the impeachment of then-President Bill Clinton, whose deception in the face of extramarital scandal might have angered more Democrats had Republicans not brimmed with hypocritical and opportunistic indignation. There was, after the brief interlude of 9/11, the Bush administration’s disastrous handling of the Iraq War and Hurricane Katrina. And there was, of course, the election of Obama, whose unifying rhetoric met with the cold realities of governing in a bitterly divided nation, stoking the flames of polarization that had come to inform seemingly every issue, even those where once considerable agreement existed.

Trump understands—intuitively, if not academically—how this atmosphere invited his emergence.

In an interview inside the Oval Office, he misses no opportunity to highlight the failures of the governing class, alternatively delighted and vexed that no politician proved capable of identifying or exploiting the opportunity he did.

The president seems particularly gleeful in swiping at his most immediate predecessors, one of each party, a merry violation of etiquette inside the world’s most exclusive fraternity. Bush, he says, “caused tremendous division . . . tremendous death, and tremendous monetary loss” by focusing on nation-building abroad instead of fortifying a wobbly domestic economy. Obama, the president argues, was even more clueless when it came to the economy, standing idly by as the country hemorrhaged blue-collar jobs, more concerned about preserving political norms than protecting American workers.

Whether fair, or accurate, or nuanced, these sentiments were undeniably shared by a sizable chunk of the American electorate in the waning years of Obama’s presidency. By stepping into the arena and presenting himself as a brawler—someone unbeholden to any special interest, someone unencumbered by the conventions of Washington, someone willing to burn down the government on behalf of the governed—Trump returned the Republican Party to power.

He also understands the relationship between his victory and the GOP’s previ

ous two losses.

The 2008 campaign was “a very rough time for the Republican Party,” Trump says. He recalls how McCain embraced Bush’s floundering war in Iraq; how he resorted to gimmicks as the global banking system teetered on the edge of the abyss; how he repeatedly told laid-off midwestern voters that some of their jobs wouldn’t be coming back. “I gave him money—believe it or not, because I wasn’t a huge fan, then or now, but I raised money for him,” Trump says of McCain. “And then he just gave up on an entire section of the country.”

The 2012 defeat was worse, because to Trump, it was avoidable. Whereas McCain had been hamstrung four years earlier by Bush’s deep unpopularity as well as a dramatic financial crisis, Romney faced a vulnerable incumbent presiding over a sputtering economy. Yet, instead of appealing to the primal instincts of the right, running a bloody campaign against a president whose team was showing no mercy to Romney, the Republican nominee played by the rules. “Romney’s problem was he had too much respect for Obama,” Trump says. “And he shouldn’t have, because Obama didn’t deserve it.”

In both cases, Trump says, these Republicans lost because they acted like, well, Republicans. McCain and Romney defended the merits of free trade, promoted the exporting of American military force, and advocated the importing of cheap labor—all while adhering to a code of conduct that pacified the graybeards of the GOP establishment.

What Trump does not understand is that his populist, inward-facing “Make America Great Again” mantra is less a revelation than a resurrection. For generations, his ideological forebears—from Ohio senator Robert A. Taft, to the leaders of the John Birch Society, to “Pitchfork” Pat Buchanan, who challenged George H. W. Bush in the 1992 GOP primary—have peddled a version of conservatism, known commonly as paleoconservatism, anchored by an intense skepticism of international commerce, military adventurism, and foreign immigration.

As a political philosophy, this brand of right-wing nationalism was crushed under the heel of William F. Buckley’s National Review, the Ronald Reagan revolution, and the Bush dynasty. In pursuing a vision of expansionist, growth-oriented neoconservatism, these forces transformed the post–World War II Republican Party into a champion of global markets, global policing, and global citizenry.

American Carnage

American Carnage